Beyond Finances, Part 4: Stewards of the Mysteries of God

04 Jul 2023 - Michael Hess II

Note: Throughout this series, I am using the English Standard Version (ESV) unless noted otherwise. If you are looking up texts in your own Bible as you read, you may notice differences in key words and phrases. Sometimes this just means the underlying Greek text can be translated more than one way. I will discuss one such term in the following paragraphs. Other times, differences may arise from variant readings in the Greek. Such variants affect two of the verses I will cite. If you are reading from the KJV or NKJV, you will not find a word equivalent to steward or stewardship in these two verses. In both cases, the Textus Receptus used by the KJV translators has a different word than most Greek manuscripts (the Textus Receptus is usually close to the majority text, but these are two of the exceptions). In each case I will add a footnote with a more detailed explanation. If you prefer the TR/KJV reading, that’s fine. The rest of the passages cited are more than enough to support my main points.

In Part 3 we saw how Jesus uses the language of stewardship for both Himself and the people He entrusts with spiritual leadership. He is the Chief Steward, opening the door of salvation. We are His understewards, distributing spiritual food by proclaiming the Word of God. Paul picks up this motif in his letters, eloquently describing and synthesizing both roles.

This installment will focus on how the New Testament epistles use the words oikonomos and oikonomia, introduced in Part 2. Oikonomia had a wide range of meanings in antiquity and acquired more over time. Its basic meaning had to do with household management, but ancient writers expanded its usage to include an orderly arrangement of parts of a system, the administration of a city-state, and even divine regulation of the universe.1 As a result, while stewardship is often a good translation of oikonomia, it is not the only one, and in some contexts not even the best one.

Other words English Bible translators sometimes choose to translate oikonomia include plan, administration, and dispensation. The last term merits a little more attention. Dispensation, related to the verb dispense, came into English from Latin. The Vulgate used dispensatio to translate oikonomia, which no doubt influenced early English translators to use dispensation. Dispensation occurs four times in the KJV, accounting for about half the uses of oikonomia. It’s not a bad choice, as long as we take care to distinguish which meanings of dispensation make sense in context and not to read back into the text other ways the word is used today.

One meaning of dispensation is simply “the act of dispensing”.2 This overlaps with aspects of a household manager’s job, which involves “dispensing” food and other necessities to the members of the household—or, in the spiritual sense we’ve been discussing, “dispensing” the word of God to other people. This meaning works well in several of the stewardship texts we will read. Another relevant definition is “a general state or ordering of things”,3 which is probably closer to the intended meaning in some other texts. Throughout church history, both oikonomia and dispensation have picked up additional theological meanings.4 While studying those historical developments is useful, this article will focus on New Testament usage.

Enough preamble; let’s look at the texts!

Ephesians: “A Plan for the Fullness of Time”

Paul’s letter to the Ephesians uses oikonomia to refer to both God’s work and his own, making it a good starting point for our discussion. He opens the letter with a beautifully-worded description of God’s predestination—not an arbitrary, freedom-canceling determination, as some would take it, but a loving, thought-out plan for our salvation. The center of this plan is Christ.

In him we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of our trespasses, according to the riches of his grace, which he lavished upon us, in all wisdom and insight making known to us the mystery of his will, according to his purpose, which he set forth in Christ as a plan for the fullness of time, to unite all things in him, things in heaven and things on earth.

(Ephesians 1:7–10)

|

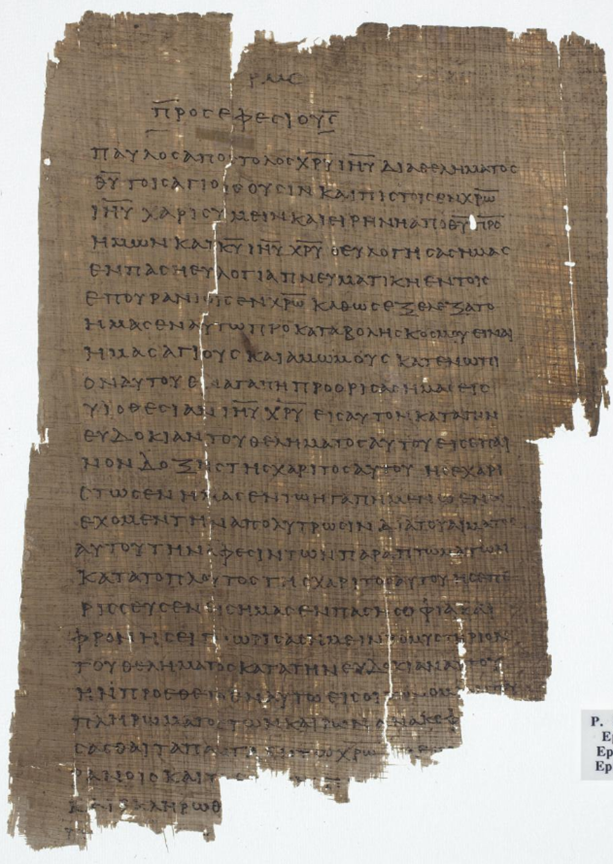

| The first page of Ephesians from P46, an early papyrus manuscript containing Pauline letters |

The word plan (KJV dispensation; NASB1995 administration) is translated from oikonomia. Paul uses this word to highlight the fact that salvation is built into God’s overarching plan for the universe. Just as in Part 3 we saw that Jesus is the chief Steward of His own kingdom, so here we find that Jesus and the Father manage the oikonomia of the cosmos. God’s relationship to the stewardship of His domain is not careless like Potiphar’s, nor self-opposing like Ahab’s; instead, like Abraham, He takes an active, intentional role in its administration (see Part 2).

(For an enriching exercise, read through Ephesians 1 and 2 and note all the ways Paul refers to God’s intentionality.)

Paul later takes the same word he used to describe God’s cosmic plan and uses it to describe his own role:

For this reason I, Paul, a prisoner of Christ Jesus on behalf of you Gentiles—assuming that you have heard of the stewardship of God’s grace that was given to me for you, how the mystery was made known to me by revelation, as I have written briefly. … This mystery is that the Gentiles are fellow heirs, members of the same body, and partakers of the promise in Christ Jesus through the gospel.

(Ephesians 3:1–3, 6)

The stewardship entrusted to Paul involves sharing the gospel revealed to him, specifically the good news that the Gentiles have a share in God’s kingdom—or, we could say, in God’s economy. While Paul is using oikonomia in a different sense here than he did in 1:10, I think he intends them to be connected, especially since he goes on to say that his work is “to bring to light for everyone what is the plan [oikonomia] of the mystery hidden for ages in God” (3:9).5 By playing on two different senses of the word, he brings out the relationship between his work and God’s. The plan of salvation, including the reconciliation of the Gentiles, belongs to God, who takes personal charge of ordering the universe and caring for its inhabitants. Within that larger plan, Paul has a stewardship role of sharing God’s word and God’s grace with God’s people.

Ephesians anchors the principle of stewardship—as it does many other themes—in heavenly realities. Other letters from Paul expound on practical implications of having a stewardship role under God.

1 Corinthians: “Stewards of the Mysteries of God”

In 1 Corinthians, Paul addresses a number of problems occurring in the church at Corinth. The first issue he tackles is division and quarrelling as the believers form factions: “each one of you says, ‘I follow Paul,’ or ‘I follow Apollos,’ or ‘I follow Cephas,’ or ‘I follow Christ” (1:12). Paul goes to great lengths to show the folly of such arguing, pointing out that he and Apollos and all the rest are merely servants doing their assigned work (3:5). The work is not their own: they are God’s fellow workers; the Corinthians are God’s field and God’s building (3:9).6

Paul continues his argument with a statement we saw at the beginning of this series: “This is how one should regard us, as servants of Christ and stewards of the mysteries of God. Moreover, it is required of stewards that they be found faithful” (1 Corinthians 4:1–2). Paul is emphasizing that he and Apollos are not anything special of themselves. They are simply servants and stewards. The Corinthians must not lose their unity and focus on Christ by putting His stewards on pedestals—a lesson that still holds true for today’s celebrity preacher culture.

As in Ephesians and elsewhere, Paul refers to the message he bears as a mystery because it was previously unknown (see Ephesians 3:4–5). In 1 Corinthians, Paul has already expounded on the nature of the—now revealed—mystery.

Howbeit we speak wisdom among them that are perfect: yet not the wisdom of this world, nor of the princes of this world, that come to nought: But we speak the wisdom of God in a mystery, even the hidden wisdom, which God ordained before the world unto our glory: Which none of the princes of this world knew: for had they known it, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory. But as it is written, Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man, the things which God hath prepared for them that love him. But God hath revealed them unto us by his Spirit: for the Spirit searcheth all things, yea, the deep things of God.

(1 Corinthians 2:6–10, KJV)

As a steward of God’s mysteries, Paul has a responsibility to share the things God has revealed to him, previously unknown to his audience. Paul does not say this in a spirit of elitism or as though he had some exclusive access to hidden knowledge (“For just two drachmae, get your copy of Apostle Paul’s 10 Things Your Priestess Doesn’t Want You to Know!”). Rather, he repeatedly emphasizes that God is the one revealing the mystery through His Spirit (mentioned throughout verses 10–15). Because Paul knows what God has revealed, he has a duty to share it.

Paul’s concept of stewarding God’s now-revealed mysteries bears resemblance to the idea of “present truth” as used by early Adventists. Like Paul, the Adventist pioneers saw themselves as entrusted with a message especially relevant to their time, truths that—though they had been true all along—had been forgotten or neglected, and that God was now bringing back to the world’s attention in a special way. This conviction bore itself out in several distinctive Adventist emphases, such as the reality of the sanctuary in heaven and Jesus’ high priestly work there, the importance and significance of Sabbath rest, and the Great Controversy metanarrative. Their theological beliefs also drove them to take a stand on some of the hot-button social issues of their time, including abolition and temperance. Much of the Adventist sense of identity and mission comes from Daniel and (aptly-named) Revelation, books especially focused on revealing the mysteries of God and that we believe have special significance for our era. Like Paul, our knowledge of what God has revealed propels us, as good stewards, to share it with the world. Also like Paul, we must always remember that mere knowledge is not what matters, instead keeping the focus of everything we share on “Jesus Christ and him crucified” (1 Corinthians 2:2).

Paul’s concept of stewarding God’s now-revealed mysteries bears resemblance to the idea of “present truth” as used by early Adventists. Like Paul, the Adventist pioneers saw themselves as entrusted with a message especially relevant to their time, truths that—though they had been true all along—had been forgotten or neglected, and that God was now bringing back to the world’s attention in a special way. This conviction bore itself out in several distinctive Adventist emphases, such as the reality of the sanctuary in heaven and Jesus’ high priestly work there, the importance and significance of Sabbath rest, and the Great Controversy metanarrative. Their theological beliefs also drove them to take a stand on some of the hot-button social issues of their time, including abolition and temperance. Much of the Adventist sense of identity and mission comes from Daniel and (aptly-named) Revelation, books especially focused on revealing the mysteries of God and that we believe have special significance for our era. Like Paul, our knowledge of what God has revealed propels us, as good stewards, to share it with the world. Also like Paul, we must always remember that mere knowledge is not what matters, instead keeping the focus of everything we share on “Jesus Christ and him crucified” (1 Corinthians 2:2).

Paul returns to the theme of stewardship later in the letter while talking about rights. The church seems to have had an issue regarding eating food offered to idols. Paul says that while we know such offerings are meaningless, they could still defile the conscience of those without such knowledge, and we should “take care that this right of yours does not somehow become a stumbling block to the weak” (8:9). The discussion then expands to include other rights, dwelling at length on the right gospel workers have to make their living from the gospel. But while this right exists, Paul does not avail himself of it: “If others share this rightful claim on you, do not we even more? Nevertheless, we have not made use of this right, but we endure anything rather than put an obstacle in the way of the gospel of Christ” (9:12). He goes on to explain why his motivation transcends financial reward:

But I have made no use of any of these rights, nor am I writing these things to secure any such provision. For I would rather die than have anyone deprive me of my ground for boasting. For if I preach the gospel, that gives me no ground for boasting. For necessity is laid upon me. Woe to me if I do not preach the gospel! For if I do this of my own will, I have a reward, but if not of my own will, I am still entrusted with a stewardship. What then is my reward? That in my preaching I may present the gospel free of charge, so as not to make full use of [or “abuse”, see KJV] my right in the gospel.

(1 Corinthians 9:15–18)

Paul proclaims the good news about Jesus, not because he seeks payment, but because that is his responsibility as a steward. Conley Owens puts it this way:

Because of his status as a servant-steward, he receives no special accolades for preaching the gospel.

…

Surprisingly, Paul’s activity and reward are identical: to preach the gospel free of charge. The idea is not that the apostle, by refusing money, accrues merit with which he will receive a reward. Instead, by refusing money he enjoys the reward itself—the stewardship he executes, Christ working through him.7

Owens highlights both the obligation and the means inherent to Paul’s stewardship office. Paul does not demand payment because he preaches out of the obligation that comes from “his status as a servant-steward” and receives the intrinsic reward of that status. “Christ working through him” describes the means by which Paul discharges his duties, since, as Paul has already pointed out, the work really belongs to Christ.

Owens highlights both the obligation and the means inherent to Paul’s stewardship office. Paul does not demand payment because he preaches out of the obligation that comes from “his status as a servant-steward” and receives the intrinsic reward of that status. “Christ working through him” describes the means by which Paul discharges his duties, since, as Paul has already pointed out, the work really belongs to Christ.

As 1 Corinthians shows, the stewardship principle has numerous practical implications:

- The Corinthians’ focus should be on God, not Paul

- What God requires of Paul differs from worldly priorities, since Paul is a servant and steward and “the main quality demanded of such individuals was not wisdom or eloquence but faithfulness.”8

- Paul is accountable to God, not the Corinthians

- Paul’s preaching is not motivated by earthly reward

All of these implications reflect important principles that today’s gospel workers should also implement as they fulfill their God-given stewardship.

Colossians: “Given to Me for You”

Another noteworthy reference to stewardship occurs in the letter to the church in Colossae. Paul repeats many of the themes we have already seen:

… if indeed you continue in the faith, stable and steadfast, not shifting from the hope of the gospel that you heard, which has been proclaimed in all creation under heaven, and of which I, Paul, became a minister. Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I am filling up what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church, of which I became a minister according to the stewardship from God that was given to me for you, to make the word of God fully known, the mystery hidden for ages and generations but now revealed to his saints. To them God chose to make known how great among the Gentiles are the riches of the glory of this mystery, which is Christ in you, the hope of glory.

(Colossians 1:23–27)

As in the other letters, stewardship has close ties to mystery—mystery that God wants to reveal through his servants. Another repeated term is minister or servant. The Greek word is διάκονος (diakonos), also used in 1 Corinthians 4:1 and Ephesians 3:7. The English word deacon comes from this term, but in these passages Paul probably does not have the specific church office in view. The translations minister and servant both get at the broader meaning of the word, which can encompass “one who serves as an intermediary in a transaction, agent” or “one who gets something done, at the behest of a superior, assistant”.9 It’s easy to see why so many of Paul’s mentions of stewardship occur together with calling himself a diakonos—the concepts overlap and share a sense of delegated authority and responsibility.

Verse 25 contains perhaps the most concise summary of how Christian stewardship works: “… according to the stewardship from God that was given to me for you, to make the word of God fully known …” Note the components and how they map onto the principles we’ve already seen. The stewardship Paul describes …

- belongs to God …

- who gives it to Paul …

- for the sake of the Colossians …

- and entails making known the word of God.

More generally speaking, we could replace Paul with anyone entrusted with spiritual leadership and the Colossians with the people God assigns that person to serve.

The Pastoral Epistles

1 & 2 Timothy and Titus are often called the Pastoral Epistles, because Paul wrote them to people with pastoral roles and gave instructions for overseeing the church. Two of these letters mention stewards or stewardship.

At the beginning of his first letter to Timothy, Paul reminds him why he stationed him in Ephesus:

As I urged you when I was going to Macedonia, remain at Ephesus so that you may charge certain persons not to teach any different doctrine, nor to devote themselves to myths and endless genealogies, which promote speculations rather than the stewardship from God that is by faith.

(1 Timothy 1:3–4)^[10]

Apparently, some leaders in Ephesus had lost sight of their assigned task. Rather than faithfully stewarding the mysteries of God, they had become sidetracked with speculative theories. Timothy is to redirect their focus to the “stewardship from God” they should have kept in view all along. Commenting on this phrase, the Andrews Bible Commentary notes,

This has been translated in various ways. Most likely it refers to the way God manages or orders His household (cf. 3:15). Paul considered his commission to be that of a steward of God’s household (Col. 1:24–25). Thus Paul charged Timothy with the task of steering the interests of believers away from the preoccupations of the false teachers to the “way God orders things.”10

The Christian steward’s focus must remain on expounding God’s plan of salvation, and doing so with “love that issues from a pure heart and a good conscience and a sincere faith” (1 Timothy 1:5). Stewards should take this task seriously, and those who desire to teach others have a responsibility to put in the work to know what they’re talking about (1:7).

Just as Paul left Timothy in Ephesus to bring order to the church, so he did with Titus in Crete. In his instructions to Titus, he again calls church leaders stewards:

This is why I left you in Crete, so that you might put what remained into order, and appoint elders in every town as I directed you—if anyone is above reproach, the husband of one wife, and his children are believers and not open to the charge of debauchery or insubordination. For an overseer, as God’s steward, must be above reproach. He must not be arrogant or quick-tempered or a drunkard or violent or greedy for gain, but hospitable, a lover of good, self-controlled, upright, holy, and disciplined. He must hold firm to the trustworthy word as taught, so that he may be able to give instruction in sound doctrine and also to rebuke those who contradict it.

(Titus 1:5–9)

Stewards represent those they work for. The way a steward of God behaves will influence people’s perceptions of what God is like. No wonder, then, that Paul expects Titus to hold the elders to such high standards. Additionally, one’s personal character and home life reflect on one’s ability to oversee the management of God’s household (see the similar list in 1 Timothy 3, especially verses 4 & 5).

1 Peter: “The Manifold Grace of God”

If Paul’s letters were all we had, we might reasonably ask whether stewardship applies only to a select few. When writing to the churches, Paul uses “steward” to refer to himself, Apollos, and others with a special commission to spread the Word; in the Pastoral Epistles, he applies the label to elders and overseers. Are the rest of us exempt, then? Is stewardship only for those with a title and a photo in the conference directory?

Peter answers that question clearly. While his first letter does contain specific instructions to elders, he clearly intends the letter as a whole to apply to ordinary Christians, too. Addressing the letter to “elect exiles of the Dispersion” (1 Peter 1:1), he gives counsel that applies to believers in general as well as a range of specific social stations (chapters 2 & 3). Addressing his readers corporately, he says,

Above all, keep loving one another earnestly, since love covers a multitude of sins. Show hospitality to one another without grumbling. As each has received a gift, use it to serve one another, as good stewards of God’s varied grace: whoever speaks, as one who speaks oracles of God; whoever serves, as one who serves by the strength that God supplies—in order that in everything God may be glorified through Jesus Christ. To him belong glory and dominion forever and ever. Amen.

(1 Peter 4:8–11)

Peter expands the stewardship principle to encompass the multifaceted nature of the gifts God gives. God’s plan includes more than just preaching, and each person has a part to play in stewarding His grace. God intends us to use our gifts from Him to serve each other, which ultimately brings glory to God as the body of Christ grows up together (see Ephesians 4).

As Peter illustrates, an awareness of our stewardship role elevates how we think about and carry out our ministry. If we speak, it should not be on our own authority or to advance our own agenda, but “as one who speaks oracles of God”. If we provide a service, however menial it may seem, we should do it “as one who serves by the strength that God supplies”. Whatever our station, stewardship in God’s kingdom means that our work is cooperation with His eternal purpose.

Peter’s expansive application of stewardship reminds us that applying the concept to other things—like money—is not wrong in itself. When we speak of stewarding money or time or talents or the earth’s resources, we are describing biblical ideas, even if scripture doesn’t actually use the word steward when discussing them. At the same time, Peter keeps the focus of stewardship where it belongs: on Jesus Christ and the grace and glory of God. Everything else flows from that overarching priority.

Along with this focus, Peter shows that stewardship is not a role given only to apostles and elders. This passage does not come with any qualifiers on its audience, so “each” refers to rank and file Christians just as much as to leaders. All of us have the privilege and responsibility of serving as stewards in God’s kingdom.

Conclusion

In light of everything the Bible has to say about stewards and stewardship, I think we can craft a deeper, richer, and more Christ-centered statement of the doctrine than the current Adventist belief statement. Of course, any official rewrite would need the input of multiple experienced theologians, but if I were writing it the following would be my first draft:

Christian stewardship is cooperation with God in the administration of His eternal plan for His household. Father, Son, and Holy Spirit have purposed together for the redemption of humanity and the reunification of all things in Christ. Jesus occupies the role of steward in this plan, having provided the means for salvation and continuing to govern access to it. He delegates some stewardship duties to human beings. As stewards of the mysteries and manifold grace of God, believers have a responsibility to share the Word of God freely for the benefit of others, especially the good news of salvation through Jesus Christ. This applies both to church leaders, who have a special charge to preach the Word faithfully, and to lay Christians, who should employ their God-given gifts to serve each other, spread the good news, and bring glory to God. Our role as stewards encompasses everything God has entrusted to us, including time, money, possessions, and the earth’s resources. As stewards, we should ensure that our use of all these things is in harmony with God’s revealed plan and serves to advance His kingdom.

Stated in this way, Stewardship (currently Fundamental Belief #21) would have significant overlap with other belief statements, such as The Remnant and its Mission (#13) and especially Spiritual Gifts and Ministries (#17). While in some ways this would make the list redundant, it also highlights just how interconnected the truths of the Bible are. It should not surprise us if, on closer inspection, we find more in common between different doctrines than first meets the eye. After all, if doctrines are based on the same Bible and centered on the same Christ, there will naturally be recurring themes. As Ellen White put it:

The truths of the gospel are not unconnected; uniting, they form one string of heavenly jewels, as in the personal work of Christ, and like threads of gold they run through the whole of Christian work and experience.

Christ is the complete system of truth. He says, “I am the way, the truth, and the life.”11

Whether or not a General Conference session ever rewrites Fundamental Belief #21, we as members of the church can seek to apply a more holistic, biblical understanding of stewardship to our lives. This does not mean we should stop caring about how we should spend our money, but we should put finances in their proper perspective. Our culture is so money-driven that it’s hard to imagine life without it, but the reality is that money is a human invention that will ultimately fade away. Eternal principles do apply to our temporal lives, including how we handle money. But the mammon of unrighteousness should never take our focus off the kingdom of God and His righteousness.

As good stewards of the mysteries of God and of His varied grace, seek to carry out the part of His plan He has delegated to you. If you are a pastor, elder, or teacher, take seriously the task of equipping yourself for ministry and of proclaiming the Word of God. If you are a lay member, prayerfully examine the gifts God has given you and consider how you can use them to build up His body and carry forward His work. Study the lessons of stewardship from the Bible and apply them to your own life and ministry.

Be like Eliezer. Cultivate a deep relationship with your Master, represent Him faithfully, and do your assigned part to fulfill His plan.

Be like Joseph. Carry out your work and ministry with wisdom and foresight, faithfully overseeing the kingdom resources entrusted to you and ensuring those in your charge receive their “food in due season” (Luke 12:42, NKJV).

Be like Obadiah. Remember where your true allegiance lies, even under adverse circumstances. Provide for the people of God, and help those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake.

Be like Eliakim. Show parental-like love to those entrusted to your care, and represent Christ with your life and actions.

Above all, imitate Jesus.

Footnotes

-

John H. Reumann, Stewardship & the Economy of God (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 1992), p. 11–15. ↩

-

Merriam-Webster, dispensation, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/dispensation. Accessed June 24, 2023. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

See Reumann, Stewardship & the Economy of God, for a fuller discussion. ↩

-

The KJV reads “fellowship of the mystery” in this verse. Almost all Greek manuscripts have οἰκονομία here, including some of those available to Erasmus when he compiled the Textus Receptus. For some reason, he chose to follow a manuscript with κοινονία (fellowship) instead. The two words look and sound similar enough that it’s not hard to imagine how a hasty scribe could have confused one for another, but the manuscript evidence is overwhelmingly in favor of οἰκονομία. For an accessible discussion of this verse, watch https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PMdiI6e7M34&ab_channel=MarkWard. ↩

-

The emphasis on God in 3:9, already clear from the context and repetition, is further reinforced by the fact that in Greek all three phrases begin with θεοῦ (God’s). ↩

-

Conley Owens, The Dorean Principle: A Biblical Response to the Commercialization of Christianity (Dublin, CA: FirstLove Publications, 2021), p. 49, 50. ↩

-

Andrews Bible Commentary, New Testament (Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press, 2022), p. 1623. ↩

-

Walter Bauer, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, rev. and ed. Frederick W. Danker, 3rd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 230. ↩

-

Andrews Bible Commentary, 1788. ↩

-

Ellen White, Manuscript 34, 1894, p. 6. ↩