Beyond Finances, Part 2: Stewards in Biblical History

26 Mar 2023 - Michael Hess II

When Jesus and the New Testament authors discuss stewardship as a spiritual concept, they are making an analogy from the work of literal human stewards. In order to understand the significance of this metaphor, it will help to review what stewards actually do. This post will look at several examples of stewards throughout the Bible. This survey from Abraham to Paul covers a vast stretch of time, encompassing many cultural, political, and economic upheavals. But while the details of a steward’s role may have adapted to different contexts, we will observe several common themes that remain true throughout ancient history.

It will be helpful to keep in mind the meaning of the modern English word steward. Here’s the full definition of the noun from Merriam-Webster:

1 : one employed in a large household or estate to manage domestic concerns (such as the supervision of servants, collection of rents, and keeping of accounts)

2 : shop steward

3 : a fiscal agent

4 a : an employee on a ship, airplane, bus, or train who manages the provisioning of food and attends passengers

b : one appointed to supervise the provision and distribution of food and drink in an institution

5 : one who actively directs affairs : manager

Keeping the meaning in mind will help us recognize instances of stewardship even if the word does not appear in an English translation (although it will in many cases).

Eliezer of Damascus

I wasn’t sure at first whether to include Abraham’s servant Eliezer in this list. While the KJV has Abraham calling him “the steward of my house” in Genesis 15:2, the Hebrew phrase is obscure and most modern translations render it as “the heir of my house”, which makes good sense in context. Genesis 24:2, however, refers to the servant Abraham sent to find a wife for Isaac as the one “who had charge of all that he had”, indicating a stewardship role. I will assume the traditional identification of this servant as Eliezer, although most of the following observations do not rely on that conclusion.

As the oldest servant of Abraham’s household (24:2), Eliezer has spent a lifetime building his track record. The level of trust Abraham has in him shows clearly in the mission he sends him on. The way Eliezer conducts himself as Abraham’s representative will reflect on his master’s reputation, for good or bad. The mission itself has several layers of importance. Of course, the bride he selects will have an impact on Isaac’s well-being, as well as that of Abraham. The choice also matters for the preservation of the family line, a high priority in ancient cultures. Even more critical, however, is what the continuation of this line means in particular: the fulfillment of God’s promise to Abraham, not only that his own descendants would multiply, but that through the promised seed “all the nations of the earth [shall] be blessed” (Genesis 22:18).

This story highlights the deep trust and family-like intimacy between Abraham and Eliezer. Given what Eliezer proved himself worthy of, it is no wonder that Abraham chose him to be in charge of all his possessions. It is also easy to see why, before Abraham had a son of his own, Eliezer was the one to whom he had planned to entrust his legacy (Genesis 15:2–3). As other examples will show, not all stewards enjoyed quite the same level of trust and closeness that Eliezer did. But his relationship with Abraham clearly gave him unique qualification for the role and helped ensure his success in it.

Joseph and Joseph’s Steward

Throughout the twists and turns of the Joseph story, at least three examples of stewardship appear: Joseph as overseer of Potiphar’s estate, Joseph as governor of Egypt, and the steward of Joseph’s own household.

Genesis 39:2–6 describes the role Joseph had under Potiphar:

The LORD was with Joseph, and he became a successful man, and he was in the house of his Egyptian master. His master saw that the LORD was with him and that the LORD caused all that he did to succeed in his hands. So Joseph found favor in his sight and attended him, and he made him overseer of his house and put him in charge of all that he had. From the time that he made him overseer in his house and over all that he had, the LORD blessed the Egyptian’s house for Joseph’s sake; the blessing of the LORD was on all that he had, in house and field. So he left all that he had in Joseph’s charge, and because of him he had no concern about anything but the food he ate.

Like Eliezer, Joseph achieved a position of extreme trust and responsibility. But while Abraham’s trust in Eliezer came intertwined with his own intentionality and involvement, Potiphar’s reliance on Joseph comes across as much more hands-off, possibly even negligent. As John Wesley wryly remarks, “The servant had all the care and trouble of the estate, the master had only the enjoyment of it; an example not to be imitated by any master, unless he could be sure that he had one like Joseph for a servant” (source).

What Eliezer’s and Joseph’s situations had in common was that both their roles extended far beyond bookkeeping. As steward of Potiphar’s household, Joseph’s authority extended to “all that he had, in house and field.” But handling money is only one aspect of running an estate. Joseph would also have been responsible, whether himself or through servants under him, for directing workers, maintaining the house and grounds, planning improvements or new acquisitions, keeping track of supplies, housing guests, and ensuring that everyone had enough to eat.

That last item would later become Joseph’s primary job for the whole kingdom. After demonstrating his capabilities in Potiphar’s house and in prison, Joseph, through God’s arrangement, came to the attention of Pharaoh and proposed a plan to sustain the people through the coming famine. Pharaoh gave him authority to carry out this plan, telling him, “You shall be over my house” (Genesis 41:40)—a phrase very similar to a common title for stewards (see below). Pharaoh continued, “and all my people shall order themselves as you command. Only as regards the throne will I be greater than you … without your consent no one shall lift up hand or foot in all the land of Egypt” (41:40, 44). Even allowing for the obvious hyperbole, Joseph’s role clearly encompassed a vast scope of authority. Pharaoh’s purpose in giving him this power was to ensure he had full ability to perform his essential task: making sure everybody had food. This involved phases of planning, organizing, collecting, and distributing, all of which Joseph performed successfully.

As the plot thickens in the story of Joseph and his brothers, we meet Joseph’s own household steward. This unnamed man first appears in Genesis 43:16: “When Joseph saw Benjamin with them, he said to the steward of his house, ‘Bring the men into the house, and slaughter an animal and make ready, for the men are to dine with me at noon.’” Throughout this story, the phrase translated “steward” or “steward of [Joseph’s] house” is אֲשֶׁר עַל־בֵּית (asher al-beth). This phrase (or asher al-habbayith, with the article הַ) is literally “[the one] who is over the house”, and appears as a title of all the rest of the Old Testament stewards we will consider.

Right away, we see Joseph’s steward in charge of welcoming guests and arranging food. Throughout the story, he also handles money (43:23), assists his master’s devious experiment (44:1–2), and even chases down accused thieves to recover stolen property (44:3–13). Once again, stewardship involves a high degree of delegated authority, to be used in assuring the well-being of the household.

Obadiah

Centuries later, while Ahab reigned over Israel, the land went through a severe drought and famine. It got so bad that the king personally set out in desperate search of grazing land for the animals. To aid him, “Ahab called Obadiah, who was over the household [asher al-habbayith]” (1 Kings 18:3). As the royal steward, Obadiah shared responsibility with the king for the management of his affairs, including caring for livestock.

The narrator informs us that “Obadiah feared the LORD greatly, and when Jezebel cut off the prophets of the LORD, Obadiah took a hundred prophets and hid them by fifties in a cave and fed them with bread and water” (18:3–4). The text does not say where Obadiah acquired this food, but it seems likely that it would have come from the royal storehouses. As king of Israel, Ahab should have been defending Yahweh’s prophets instead of allowing his wife to exterminate them. Obadiah acted on what should have been the king’s behalf in caring for the prophets. Ironically, faithful stewardship in this case involved going behind his master’s back, acting on his true allegiance to a higher King, Yahweh—which Ahab ought to have shared.

Shebna and Eliakim

Isaiah 22 contains several scathing rebukes against unfaithful leaders of besieged Jerusalem. Many of those tasked with defending the city had tried to escape (Isaiah 22:2–3). Others who should have been leading the people in repentance were instead indulging themselves with feasting (12–13). The sternest words are directed toward an individual:

Thus says the Lord GOD of hosts, “Come, go to this steward, to Shebna, who is over the household, and say to him: What have you to do here, and whom have you here, that you have cut out here a tomb for yourself, you who cut out a tomb on the height and carve a dwelling for yourself in the rock?” (15–16)

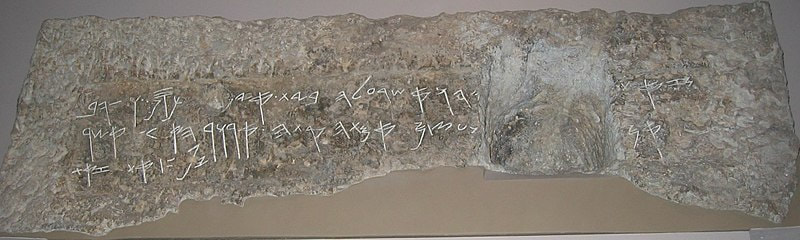

|

| Image of the Royal Steward inscription from Wikimedia Commons |

Instead of doing his job as steward and caring for the royal household, Shebna has wasted resources on an extravagant memorial tomb for himself. The Royal Steward inscription, found near Jerusalem in 1870, marks the tomb of an asher al-habbayith. While the name has broken off the inscription, some scholars believe this may refer to Shebna’s tomb. Shebna’s unfaithfulness will reap severe consequences:

Behold, the LORD will hurl you away violently, O you strong man. He will seize firm hold on you and whirl you around and around, and throw you like a ball into a wide land. There you shall die, and there shall be your glorious chariots, you shame of your master’s house. I will thrust you from your office, and you will be pulled down from your station. (17–19)

The passage then transitions to Shebna’s replacement:

In that day I will call my servant Eliakim the son of Hilkiah, and I will clothe him with your robe, and will bind your sash on him, and will commit your authority to his hand. And he shall be a father to the inhabitants of Jerusalem and to the house of Judah. And I will place on his shoulder the key of the house of David. He shall open, and none shall shut; and he shall shut, and none shall open. (20–22)

God Himself appoints Eliakim to the office of royal steward. Unlike Shebna, Eliakim will faithfully carry out his responsibilities, becoming a “father” to the people. The key (much larger than modern keys, hence being placed on the shoulder) symbolizes “his administrative authority to make decisions”.1

Later events show the fulfillment of this prophecy. During the face-off with Sennacherib described in Isaiah 36–37 and 2 Kings 18–19, the text repeatedly refers to Eliakim, not Shebna, as the one “who was over the household”, while describing Shebna as a scribe or “secretary”. Assuming this is the same Shebna as in Isaiah 22, it appears that his predicted death did not happen immediately. Instead, God let him live long enough to see the rest of the prophecy come true—his own demotion and Eliakim’s ascension to his office.

New Testament Stewards

While the New Testament more explicitly touches on the theology of stewardship than does the Old Testament, it contains relatively few references to literal stewards. It uses two words with overlapping meanings: ἐπίτροπος (epitropos), “one to whom the charge of anything is entrusted, steward, trustee, administrator”; and οἰκονόμος (oikonomos), “one who manages a household … steward of an estate” (you can read the full definitions from the Liddell-Scott-Jones lexicon here and here). Of these, oikonomos is much more common in the New Testament, and also often appears in the Septuagint as a translation of asher al-habbayith.

Both words appear in Galatians 4:2, which says that a child heir “is under guardians [epitropos] and managers [oikonomos] until the date set by his father.” Paul is using an illustration from the culture of the time to make his point. This gives us a glimpse of the wide range of roles that could fall under the title of oikonomos, or household manager/steward.

In the Greco-Roman world, the oikos (house, family, or household) was the basic unit of society. The management of a household was called oikonomia, and was the role of the oikonomos, who was often the head of the household but could also be a high-ranking servant, as the next story illustrates (see Wikipedia for a more extensive overview and references).

Luke 16 records Jesus’ parable about a dishonest oikonomos, translated as “steward” in the KJV and “manager” in the ESV. Like many of Jesus’ parables, this one draws on a true-to-life scenario—in fact, Ellen White says that “There had been among the publicans just such a case as that represented in the parable, and in Christ’s description they recognized their own practices” (Christ’s Object Lessons, 368). The next installment of this series will look at the spiritual application of this parable and others; for now I want to focus on what we can observe about the steward’s role.

The rich man in the story appears almost as hands-off as Potiphar was with Joseph, not even noticing a problem until “charges were brought to him that this man was wasting his possessions” (Luke 16:1). Up until this point, the steward had enjoyed unsupervised control of his estate. As part of his duties, he had arranged to keep the pantry full, making contracts for large quantities of oil and wheat (5–7). After being dismissed from his position, he used his sharp business sense to make provision for himself. Knowing that “the families dealing with the produce noted in vv. 6–7 are themselves wealthy, and might welcome a manager with business experience who had already supported their interests”2, he sets out to earn their favor by changing their contracts. He manages to secure his goal while also making his master appear generous, winning the master’s admiration in spite of his dishonesty (verse 8).

Summary

From all these examples of stewards, both good and bad, we can draw several observations about what stewardship meant.

- A steward represented his master, running the household or kingdom on his behalf and holding authority second only to his.

- Stewards and masters could sometimes form close personal relationships, approaching that of family members.

- Masters varied widely in how much involvement they had in running their households; their reliance on their stewards varied accordingly from a blind trust to an intentional one.

- Of all the duties a steward would have had in a large household, one that figures prominently in several stories is that of caring for the people associated with the household, particularly by procuring and distributing food.

- Some stewards served for life, but this was not guaranteed; a steward could be dismissed—and suddenly—if found to be unfaithful.

Attentive readers may have already noticed a key phrase in one of these stories that Jesus later uses to describe His own work. Part 3 of this series will explore that connection and the concept of stewardship in Jesus’ ministry and teachings.

Footnotes